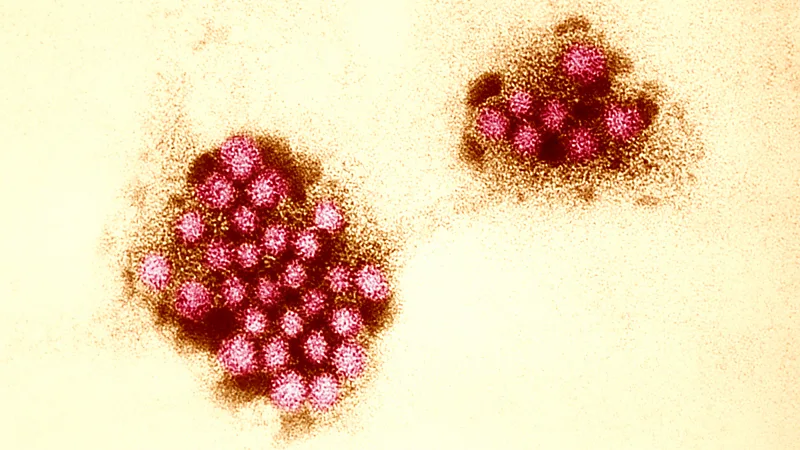

The winter vomiting bug is highly infectious and fast to evolve, but can we learn anything from groups of people who are unusually immune to the virus?

When it comes to surviving in the environment, few pathogens are more resilient than norovirus. This gastrointestinal bug induces nasty bouts of diarrhoea and vomiting in around 685 million people globally every year, often in hospitals, nursing homes, jails, schools and cruise ships.

The latest statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reveal that the germ is spreading rapidly once again across the US, with a rapid spike in outbreaks in the final weeks of 2024. It follows a dramatic spike in the virus the previous winter, where the number of cases climbed particularly quickly since October 2023 in the northeast of the US.

But to understand why norovirus is so hard to stop once an outbreak gets going, you first have to appreciate just how much it can endure. “It’s a very tough little virus,” says Patricia Foster, professor emerita of biology at Indiana University Bloomington who has studied norovirus. The virus is able, for example, to survive intact within food up to temperatures of 70C (158F). “It can survive heat, freezing cold, extreme dryness, and so it just sits on surfaces for days,” says Foster.

Much of this toughness comes down to the surface of the virus, a protein coat which acts a little like armour, shielding its inner genetic material. Foster points out that while a lot of viruses acquire a membrane coat as they pass from cell to cell, facilitating their ability to spread within the body, this also makes them susceptible to alcohol and detergents.